Brien Beidler: Bookbinding, & The Case For Conservation

Words & Photographs by Ben Grenaway

“I told The Library Society that maybe they shouldn’t hire me, maybe they should hire someone who actually went to school for book-binding. I mean, I got a degree in Chemistry, but here we are, three years later and I am absolutely loving it”

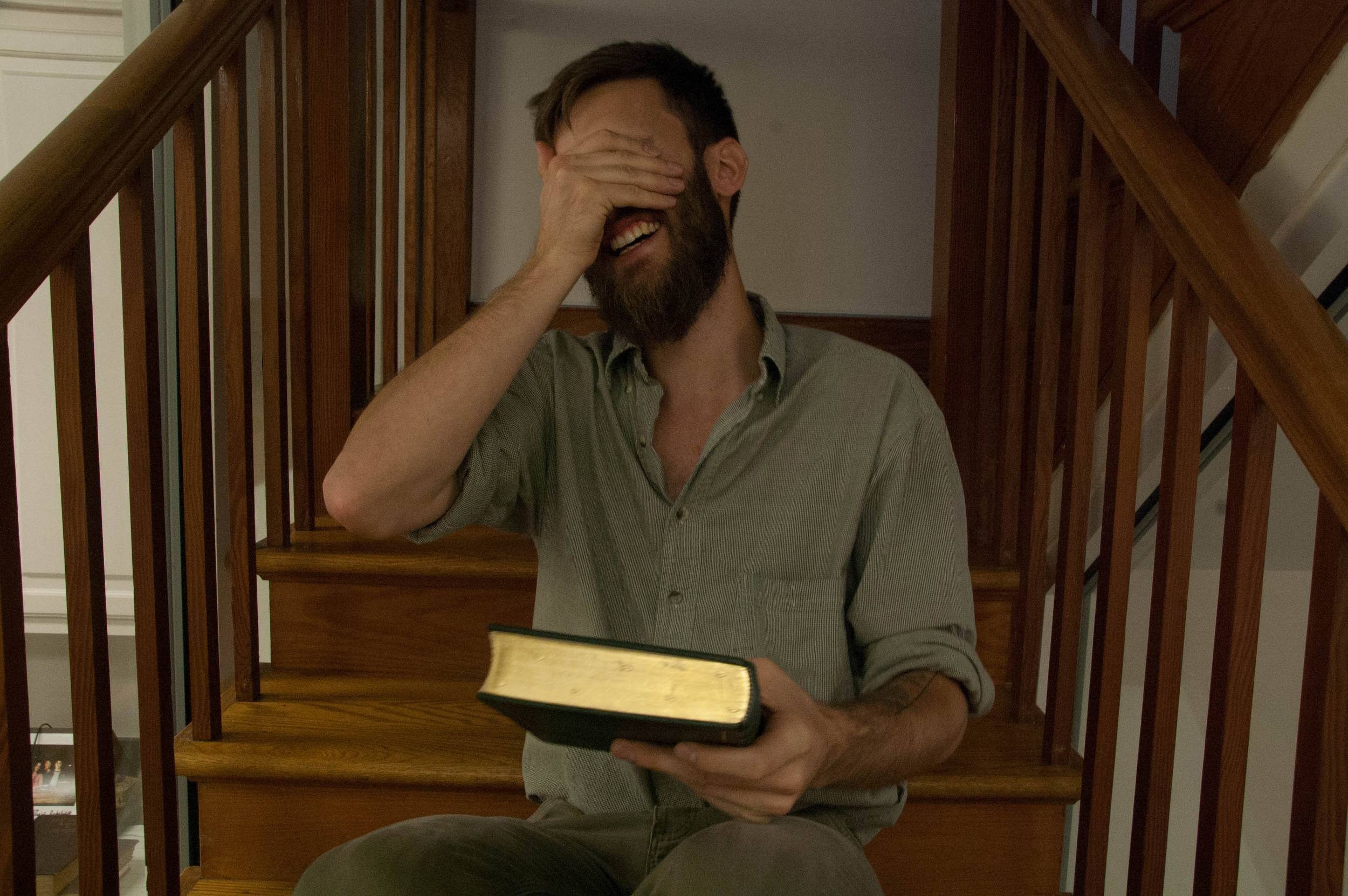

It is easy to see why the hiring director of The Library Society took a flyer on a, then 22 year old, bright eyed Brien Beidler. A warmth permeates from his thistle brown beard as he palms a book older than the library it occupies, and smiles.

“I have always wanted to do this. I have had the inexplicable passion to collect old books since I was a little kid, . One of my biggest dreams is getting my hands on an old hardback of Lord of the Rings and do some bindings. It gives me the chills even thinking about it”

Brien Beidler has worked as Charleston Library Society’s Bookbinder and Book Conservationist since 2012. While bookbinding and book conservation sounds similar, there are important differences.

Book conservationists can be thought of as literary paleontologists, preserving as much of history as possible, in the hopes that state of art techniques will allow people like Brien to tell entirely new stories of history and culture. Bookbinding is the more practical side of the book craft, rebuilding books to usable and marketable form.

For Brien, the most important step in book conservation is to first meticulously evaluate the book, contemplate the history and condition of the literature. Once that is finished, Brien works to create a gameplan to either conserve the compendium of knowledge into a polished antique or, instead, to release the book of its bindings and give frilled pages a new leather-bound home.

In short, there are a myriad of different conservation treatments. They include the careful removing and re-adhering of often cracked and brittle spines, using thin white Japanese papers of various weights to repair tattered pages or losses in leather. Beyond that, there is re-attaching covers, relining the spines, or even dis-bounding the book. If the book must be disbound, each page must be washed separately in an alkaline bath, sized, repaired and put back in order before finally being rebound.

“Each book is its own leather bound animal when it comes to the time needed for adequate repair. Time for repair can range in time from 25 minutes to 25 hours, and maybe more depending on the book.”

Brien says as he pauses before thumbing a chestnut brown novel from the nineteenth century that looks just as old as the 1841 publishing date suggests.

“See this book? Someone made an old dust jacket for it. The way that I see it, somebody truly loved this book. Pages are missing, it has stains on it, maybe they were crying and tears touched pages! It is annotated throughout. Whoever owned this book took the time to sit here and actually stitch a dust jacket. Someone had to sacrifice threads that were not cheap at the time, but they did it all for this book. I think that’s absolutely beautiful. The nostalgia of it all.”

While Brien has learned much on keeping relics alive long enough for future bibliophiles to comb through, he admits that there is always much to learn.

“Charleston Library Society has been kind enough to send me to conventions to hone my craft. The Guild of Book Workers is a great one. It is a conglomerate for bookbinders, book conservationists and book lovers. They have a conference every year, knowledgable people from all over the world come to learn and give out information. I had heard mythical stories about this bookbinder named Jim who lives in the woods and makes all of his tools and materials from scratch. I met him at the conference and I freaked out! He has a cult following. He looks pretty rough, you wouldn’t know he was a big deal just by looking at him. Some might think that Jim’s stuff would look less than ideal since he makes it all from scratch. The thing is, his stuff is not tacky, they are masterpieces.“

As Brien tours through his underground workshop, he speaks on how his chance encounter with mystical bookbinder Jim has contributed to his process.

“I want to learn as much as possible about homesteading, self sufficiency is my ideal. I make recipes for traditional sealing wax, hand tools, and other things. We use this knife for pairing leather, but it used to be a power hacksaw blade.”

He smiles mischievously.

“I ground it down, sharpened it, and fashioned a case. In the same vein of rebinding a book, I get the same nostalgic vibe from using my own handmade tools instead of buying them. I made these bone tools as well, when I first got them they still had meat on them. From boiling it down, to shaving, to polishing, it takes a lot of work but we use these guys every single day.”

He stops, runs a smooth end of a buffalo bone across his hand, and looks out the small sun-lit window pane.

“It’s amazing, I am using animal bone to rebuild a book that was already bound in animal skin. I get to use the whole animal in a way that society has forgotten how to do.”

The era we live in is unique for bookbinders, as all things paper are being replaced by less permanent electronics, at an alarming rate.

“In many ways, electronics have done much to raise awareness to the craft of book conservation. There is a rising interest in how books are made by hand. I think it has helped, hether that is a short or long term phenomenon, it fills me with joy that people are gaining interest. There is a certain energy in older hand-made things, I think there will always be an appeal for having it done the old way.”

Brien Bidler stays hopeful that his lifestyle of conservation and home-steading continues on and spurs other self-spun movements, allow people to stop for a second and consider that the eons of human knowledge they may be holding are sure worth protecting.

For more information on bookbinding and Brien, visit his website here.